Nicole Bretherton reckons the noise is like someone starting up a lawn mower and pushing it through her lounge every few minutes.

"It's just debilitating," Bretherton said, describing a relentless wall of nerve-jangling sound she lives under from planes taking off and landing at Brisbane Airport.

The airport operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week, so aircraft can arrive and depart at any time, and recent runway changes have ramped up noise impacts.

"It's like having a headache, a constant headache, and it wears you down," Bretherton said.

"Your mental health takes a hiding because you just can't escape it. You have interrupted sleep. You can't concentrate. You can't relax. I feel irritated. I'm tired. I'm cranky.

"And then you've got things like lack of sunshine, of fresh air, because we rarely want to sit outside anymore."

Along with her husband, Bretherton, 52, lives in Hamilton, a riverside suburb in Brisbane's north-east, about 5.5km south-west of the airport.

They've owned their home for 10 years, but the noise only really became problematic when a second runway was opened in July 2020.

When that happened, doubling the airport's flight capacity and creating a series of new flight paths over large swathes of the city, the noise quickly got unbearable for her.

But Bretherton is far from alone.

Complaints from Brisbane residents about the noise have exploded since the opening of the runway, which injects an estimated $1 billion to Queensland's economy every year.

At peak times, planes take off and land every few minutes. There is no curfew at Brisbane Airport, so aircraft buzz through the night.

Every morning at 2.50am, an Emirates Boeing 777-300ER takes off from Brisbane, bound for Dubai, waking Bretherton from her sleep.

"The house shakes some nights," Bretherton said.

"I'll be lying in bed ... and I can feel it."

She admits to sometimes second-guessing herself, questioning if she's somehow lost context and become obsessed with the noise.

"But then I have people over sometimes and they're just like, 'Oh my God, how do you live with this?'"

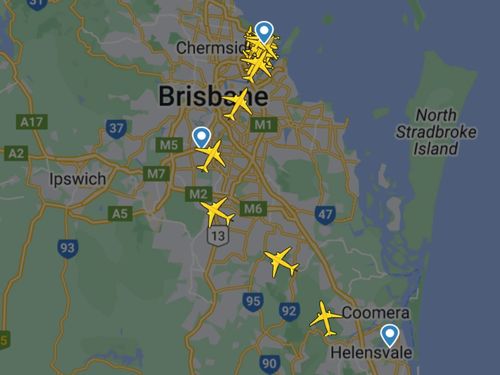

The second runway not only doubled down on the number of planes moving each day, but it created new flight paths above many suburbs that were never previously affected.

Illustrating the problem, data from the national aviation noise watchdog reveals complaints about noise have been made from 226 suburbs across Brisbane since the second runway opened.

Numbers are an important part of this story.

In August, there were 17,828 aircraft movements at Brisbane Airport, an average of 575 flights per day.

While some think that's already too much, they will need to brace for a significant increase in air traffic at the airport over the next 15 years.

The Brisbane Airport master plan has projected flight movements to grow from around 213,000 in 2020 to almost 380,000 by 2040.

The plan estimates just under 250,000 flight movements this year, which means the path to 2040 will bring a 50 per cent increase in air activity.

It's no wonder airport noise has become a citywide and political issue.

'Screw with the sleep of a whole population'

Ahead of next year's state election, the Greens have called for a night curfew and hourly flight cap at the airport, similar to rules Sydney Airport must abide.

But Deputy Premier Steven Miles has blasted those proposals, claiming it's only "wealthy inner-city elites" who don't want planes flying over their neighbourhoods, at the expense of business, jobs and industry in the state.

Melanie Stott, a mother-of-two, said aircraft noise had never been a problem in the two decades she has lived in Toowong, which lies around 15km south-west of the runways.

But, like Bretherton, that changed when the second runway went operational.

"The whole argument of 'don't buy in that area if you don't want to be disturbed by planes' doesn't apply to us because we have owned property here for a long time," Stott said.

Stott describes a particular flight that soars above her home at the same time each night "that seems to almost rattle our windows", waking up her and her husband.

"I think about our own family, but I also think of it as a whole wider population problem," she said.

"Like what are we going to do if we consistently screw with the sleep of a whole population? It's not healthy for people.

"I understand that in a big city you need to be able to have planes taking off," Stott said, but she questions why more planes don't take off and land over Moreton Bay, instead of using flight paths over the city and its population of 2.5 million.

"We definitely needed a second runway. I'm not saying we should shut it all down and not have any planes. But they just need to run (the planes and flight paths) over the bay."

Both of Brisbane's runways allow for planes to take off and land over Moreton Bay, a directional mode which significantly reduces noise pollution.

But there's a catch.

That mode of operation - known as simultaneous opposite direction parallel runway operations, or SODPROPS - can only be used at the airport during the night, and only if strict weather and flying conditions allow, including wind speed, visibility and rain.

If those environmental factors don't align, air traffic control instead directs jets and planes on a variety of routes over city suburbs.

Airservices Australia is the federal agency charged with deciding what modes of operation run at Brisbane Airport each day.

A spokesperson told 9news.com.au Airservices "is committed to improving noise outcomes for the Brisbane community, where safe and operationally feasible".

They added Airservices would like to use SODPROPS much more often.

But as it stands, SODPROPS is hardly ever operational.

In June-August, SODPROPS was used for an average of 3.4 per cent of all Brisbane Airport flights, 9news.com.au can confirm, due to restrictions.

"Safety is Airservices' number one remit," the spokesperson said.

They confirmed the agency is looking into ways it can make SODPROPS the priority mode 24/7, instead of its current night-time only use.

'Community is collateral damage'

Airservices said it also considering other noise reduction measures, including sharing airspace with RAAF Base Amberley and redesigning flight paths to reduce frequency and concentration of planes over residential areas.

Nikki Holmes, who lives in an apartment building in East Brisbane, close to The Gabba, sleeps every night with earplugs.

She talks about "constant noise" and being fatigued in the morning.

"Everyone has the right to live in their home. It's supposed to be a safe place and your sanctuary, and thousands and thousands of people (in Brisbane) don't have that."

It's got to the point where Holmes is considering selling. But where she would move to is a confounding question.

"The noise is a hot topic everywhere," she said.

"I've got friends that live a couple of suburbs away, and you go to barbecues on a weekend and it's a discussion everyone has, and people are sick of having the discussion but nothing's happened."

Ross, who did not want his full name used, has lived in an old timber and tin Queenslander style house, in Balmoral Hill, a "wonderful neighbourhood" in Brisbane's inner-east for 41 years.

He said his family's quality of life has been "completely destroyed" by the noise.

"We live with all windows and doors closed 24/7 (and) our outside deck and verandah have had little use in the last three years because of the noise," he said.

"The community is unfortunately collateral damage."

Ross said he felt duped during community consultation sessions while the runway was being planned, claiming officials had "deliberately downplayed the impact (the second runway and flight paths) would have on our lives".

Brisbane Airport Corporation, who purchased the airport on a 50-year lease from the Federal Government in 1997 for $1.4 billion, is staunchly opposed to any curfew or flight caps.

It argues curtailing flights will have far-reaching and serious consequences for Queensland's economy.

Losing Brisbane as a night-time airport would severely hurt national cargo and mining operations and tourism, Stephen Beckett, a spokesperson for the corporation, said.

Airservices has just completed another round of community meetings to try and address noise impacts caused by changes to Brisbane's airport and airspace.

Words: Mark Saunokonoko

Video and graphics: Polly Hanning