After more than half a year stuck in the Senate without enough support to become law, the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) has finally passed parliament after Labor struck a deal with the Greens.

While it's been touted by the government as the biggest-ever investment into affordable housing in Australian history, the policy is a little complicated, as it isn't a direct injection of funding into housing.

This is how it will work.

What is the Housing Australia Future Fund and how will it work?

The Housing Australia Future Fund is a $10 billion investment fund the government will create, with the returns each year used to create social and affordable housing.

Because it's an investment fund rather than a one-off cash injection, the theory behind the policy is that it will provide a long-running supply of housing funding for years to come.

The least affordable places to rent in Australia

How much will be invested under the HAFF?

You've probably seen the Housing Australia Future Fund touted as a $10 billion policy – but that's not how much will go directly into building new homes.

Rather, the $10 billion will go into an investment fund.

Each year, the returns from that fund – i.e. how much it earns on the stock market – will be used to fund the construction of new housing.

However, as the Greens argued during their negotiations with the government, if the fund loses money one year, that would mean there's no funding available for housing that year.

As a result, the policy was amended to guarantee a minimum housing spend of $500 million each year, regardless of the fund's performance.

In addition to paying for the construction of new homes, the government also says the fund's returns will provide:

- $200 million to repair, maintain and improve remote Indigenous community housing

- $100 million for crisis and transitional housing for women and children impacted by family and domestic violence, as well as older women at risk of homelessness

- $30 million to build housing for veterans who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness

Also as a result of negotiations between the Greens and Labor, the government announced $3 billion in direct spending on public and community housing, although these funds are separate from the HAFF.

How many new homes will be built?

The government says 30,000 new social and affordable rental homes will be built over the fund's first five years.

Who are the new homes for?

While not all of the 30,000 homes will be targeted at certain groups, some will be.

The government is promising 4000 of those homes will be for women and children impacted by domestic violence or older women at risk of homelessness.

It has also pinpointed veterans, key workers and "those most in need" as recipients of the new housing without going into more detail.

Where will the new homes be built?

We don't know exactly where all 30,000 homes will be built, but we do know every state and territory will receive at least 1200 each.

Will the HAFF fix Australia's housing crisis?

That's the million-dollar (or should that be $10 billion?) question, but really, we won't know for a few years yet.

The government obviously thinks it will make a significant dent in the crucial issue, and the policy has also been welcomed by a number of bodies, including Master Builders Australia, the Property Council, and the Community Housing Industry Association.

The Greens, despite supporting the bill in the Senate, actually say the fund won't fix the crisis and have continued to call for rental safeguards like caps or freezes.

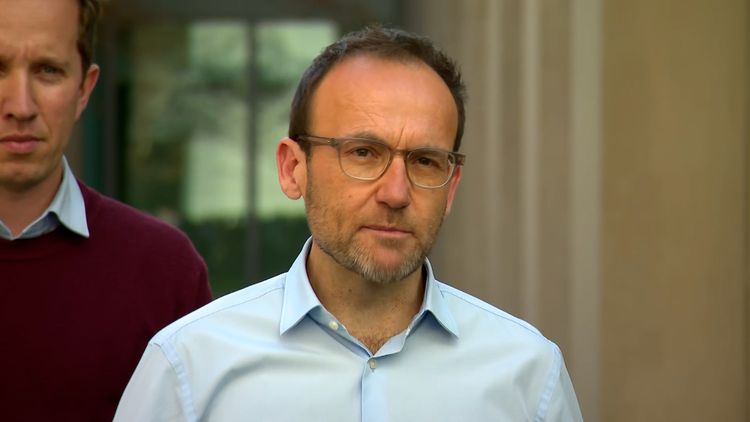

However, they've welcomed the $3 billion in direct spending this year, and housing spokesperson Max Chandler-Mather said the HAFF will provide "effectively rent-capped" properties for thousands or tens of thousands of Australians.

The opposition has consistently opposed the policy because it claims the fund doesn't do enough to support first-home buyers.

Two housing experts 9news.com.au spoke to earlier this year argued there were much better alternatives than the "contrived and convoluted" fund – although one said its passage through parliament wouldn't be a bad thing.

They instead advocated for rental caps and better regulation of short-term rentals like Airbnbs.